Key Sections

Developers—including Brookfield—have built up the park in four phases over five years.2 The first phase started before the grid had been extended to receive the power, and was largely financed by the Climate Investment Fund, the multilateral development bank founded by the G7 to co-finance climate-mitigation projects.3 For months, the panels pumped out electricity that had nowhere to go. Frequent sandstorms left layers of dust on the panels, reducing their efficiency. Now a fleet of robotic cleaning machines crawls over the site daily—the equivalent of mankind’s largest squeegee operation.4

Later phases connected Bhadla to the grid, and the development was completed in early 2021. Today, Bhadla covers 50 square kilometers5—roughly the size of Manhattan—and has 2.7 gigawatts of installed capacity.6 That is enough to power as many as 5.5 million Indian homes7 and eliminate close to 4 million tons of CO₂ per year.8 It also makes Bhadla one of the largest solar installations in the world.

If the scope of Bhadla’s undertaking strains comprehension, so does this: Compared to the 500 gigawatts of renewable capacity that the world’s most populous nation will need by 2030—and the 7,400 gigawatts it needs to meet its share of global net-zero targets by 20709—Bhadla barely grazes the surface.

As developed countries race against the clock to transition their energy from fossil-fuel to renewable sources before the planet exhausts its remaining carbon budget, emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have both less time to spare and more ground to make up. Compared to developed countries, where electricity consumption is rising due to electrification efforts and mushrooming data centers,10 EDMEs are growing their electricity demand roughly three times as fast due to their rapid economic growth.11 As it stands, EMDEs currently account for 72% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions12 (see Figure 1); new renewable capacity will need to be built at a much more rapid rate to keep pace with the ongoing development of these markets.

Figure 1: Emerging Markets Represent 72% of Global GHG Emissions (2022)

Ensuring that EMDEs get, and stay, on track will take a massive coordination on multiple fronts—each of which will rely on previously unprecedented infusions of capital. In these crucial early phases, private market investors are needed to catalyze other funding sources and crowd-in capital, including from multinational corporates intent on climate solutions for their EMDE-based operations.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), EMDEs excluding China will require a six-fold rise in clean energy investments to $1.6 trillion annually by the early 2030s13 to ensure increasing energy needs are met in alignment with the Paris Agreement. Aside from China, most EMDEs lack the public or private resources to fund their own transitions entirely. By design, development banks will only ever be one part of the mix. The G20 Independent Experts Group14 has estimated that one-third of the funding will need to come from cross-border financing.

While global private investors are increasingly seeking to invest in transition infrastructure, they have historically viewed investing in EMDE renewable energy and decarbonization projects as outside their primary scope. We believe that may be about to change.

In many emerging markets and developing economies—India, Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Turkey, Romania and more—several factors are now coming together to enable private capital to support the transition. Both capital markets and clean energy opportunities are maturing, providing investors with clearer routes for how and where to put their capital to work. And given the current imbalance between the size of the opportunity and the available capital for these regions, we believe this is resulting in an equally clear path to attractive risk-adjusted returns.

Rising Opportunities

The energy transition has scaled up rapidly over the past two decades and is now at the top of governments’ agendas. Monumental public funding in Europe, the U.S. and China has dovetailed with ongoing leaps in efficiencies and economies of scale to where the economic imperatives of renewables have taken on a life of their own. Renewable capacity added in 2023 amounted to 507 gigawatts, about 50% more than in 2022.15 Clean energy investment has risen by 40% since 2020, reaching $1.8 trillion in 2023.16

It remains to be seen whether these shifts continue to accelerate fast enough—and at a scale large enough—to prevent global warming’s most disastrous effects.

One concern has become ever more apparent: We will never reach that goal unless the source of 72% of the world’s energy-related CO2 emissions receives substantially more than 15% of the world’s renewable energy and emissions-reducing investment (see Figure 2).17

Figure 2: Emerging Markets’ Clean Energy Investment Gap

(Clean Energy Investment, GDP and Population by Region)

India is a good example of both the promise and challenges of the energy transition in EMDEs. The country, the world’s third-largest polluter, has pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2070. If India meets its goal, that achievement alone could reduce warming by 0.2 degrees Celsius.

Yet, even now, India’s economy generates 70% of its electricity from coal, and renewables contribute less than 10% of the country’s energy needs. At this point, India has approximately 182 gigawatts of renewable capacity, less than 2/100ths the amount it will need to reach its 2070 targets. That level of capacity will require a roughly $10 trillion investment between now and 2070, or $214 billion a year. That is 16 times the $13–$14 billion annually invested in India’s transition today.18

Each EMDE is different, however. India is on the more developed end of the transition spectrum and is a relatively popular destination for external financing. In countries like India, Brazil and Chile, far-sighted policy frameworks and abundant sun and wind (and in Brazil’s case, extensive hydropower) have combined to create vibrant renewable markets. In some other countries, the transition is more nascent, the challenges are different, and the gap can be wider between available capital and the amount of investment that is ultimately needed.

When sizing up the EMDE transition investment opportunity, there is no one formula or approach. Each of these markets has different characteristics based on what it is trying to achieve relative to the current state of its overall power system and energy mix. But there are common factors to consider.

The first is the growth of their overall energy usage. EMDEs’ expanding energy consumption not only raises the urgency of building out significant near-term power generation capacity, but also amplifies the opportunity to develop solar and wind projects, considered the low-hanging fruit of the global energy transition. It means there is significant potential to scale renewable energy investment in these markets.

The second is that renewables are becoming much more cost-effective in EMDEs. EMDEs benefit from the same technological advancements and rising efficiencies as developed markets. In most EMDEs, wind and solar are now cheaper and less risky on a pure capital expenditure basis to fund and deploy than fossil fuel sources are (see Figure 3).

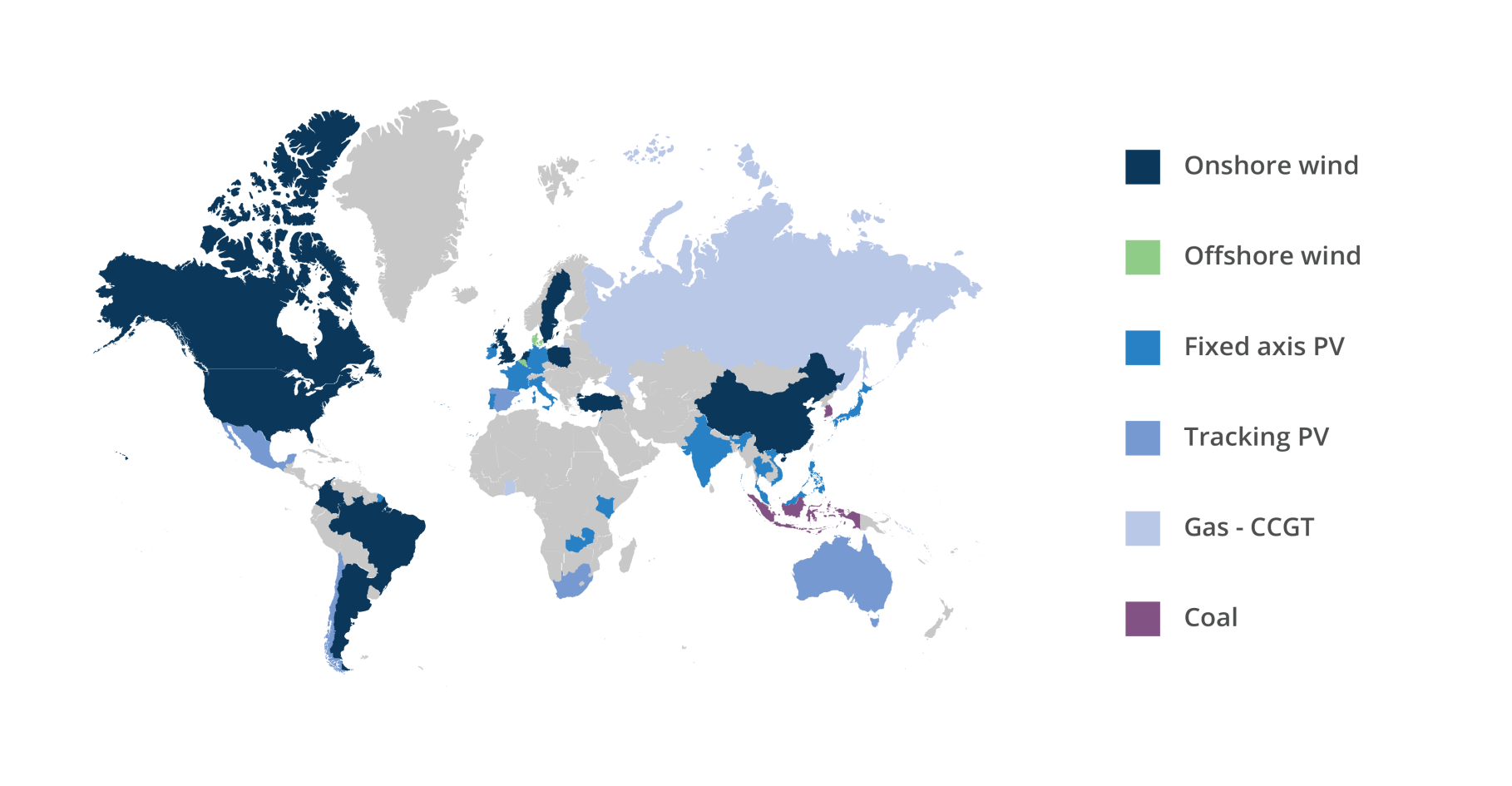

Figure 3: Wind and Solar Power Are Cheaper Than Fossil Fuels in Most Markets (1H 2023)

Cheapest new generation technology to build by market

And third is that EMDEs often have natural advantages in deploying renewables over their developed market counterparts. They are generally in higher radiation climates, many of them home to mountain, coastal or desert regions with superlative wind conditions. In Brazil, for instance, onshore wind resources are as good as offshore in the U.S. or Europe—at less than half the cost of wind power captured at sea.19

Other factors work in EMDEs’ favor as well. As illustrated by the Bhadla project, accumulating vast tracts of undeveloped land unburdened by regulatory constraints is rarely much of an issue. Equipment is often cheaper to acquire and import in these markets, and labor is typically lower cost as well, reducing the cost of construction as well as operation and maintenance (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: EMDEs Have Operation and Maintenance Cost Advantages

(Levelized Cost of Electricity for a Utility Scale Solar Plant Finalized in 2022)

Added together, these advantages have not only made renewables cheaper and more competitive than installing fossil fuel generation in EMDEs, they have also made them cheaper than developed market projects, even without the same level of government support. On average, Brookfield’s EMDE-based renewables teams have found that the estimated capital expenditures for the projects on their radar are about 40% less than equivalent-scale projects in the U.S. or Europe.

On the other hand, the EMDE transition comes with a different set of investment considerations, some real and some perceived. Yet the opportunity set is so large that investors have the ability to pick the best opportunities, where many of these risks are mitigated.

For instance, in some—but not all—of these countries, the rule of law and enforcement of contracts can be less certain than in developed market economies. Track records of local operators can be more limited, and the financial health of offtakers may be less transparent. Grid access and connection can also be complicated by inefficiencies and bureaucracy, and regulatory risk, while hardly confined to EMDEs, can be higher than in developed markets.

Currency repatriation can also be a risk for renewable infrastructure investments, especially given their long timeframes. One of the attractions to foreign investors of commodities and traditional industrial projects has been the ability to “dollarize” the investments. That is because the output is typically targeted for global markets, allowing revenues to be generated in U.S. dollars. That is not the case with renewable power, whose primary customers are homes and businesses within a country’s own borders.20

As a result, while the land, building and equipment related to an EMDE transition project may be 40% cheaper, the cost of sourcing that capital—the returns the average lender or investor demands for its risk—can be higher. For example, if the average cost of capital (including debt and equity) for a developed market solar project is around 5–6%, in EMDEs the same figure can be closer to 12% (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: The Cost of Capital Ranges for Solar and Energy Storage Projects (2022)

Despite the potential for higher returns in EMDEs, this opportunity remains chronically underfunded. Meanwhile, these countries have some of the fastest-growing and most robust economies in the world, and many of them have investment-grade ratings, supportive regulatory frameworks, a demonstrated respect for capital, strong rule of law and manageable geopolitical risk. Boots on the ground and a hands-on approach by an experienced operator offer additional margins of safety.

Given the need for a world-critical infrastructure buildout in a relatively short timeframe, the EMDE transition represents an immensely compelling opportunity for private investors—especially now that some key pieces of the puzzle are clicking into place.

Enter Blended Finance and Catalytic Capital

As with the transition itself, opening the floodgates of external capital needed for EMDE clean energy projects will require a number of steps to be taken essentially at once.

Last September, Mark Carney, Chair of Brookfield Asset Management and Head of Transition Investing, shared his recommendations for those steps in a speech at the annual G20 Summit, convened under India’s Presidency. More EMDE governments, Carney noted, need to pursue increasingly ambitious climate policies to create the right enabling environment. Uniform standards and better data are needed to track the problem. Voluntary carbon markets need to be established to accelerate cross-border flows into emission-reduction projects in EMDEs. There also needs to be a recognition that the major investors in the EMDE transition thus far—development banks—can do more to broaden the types of projects and risks that they’re willing to take on to catalyze private flows.

The world leaders gathered in New Delhi agreed with him. They unanimously recognized the need to rapidly and substantially scale up investment and climate finance from billions to trillions of dollars, particularly in EMDEs, while committing to reforms for better, bigger and more effective multilateral development banks. In pursuit of these goals, the World Bank has set up a Private Sector Investment Lab to provide the Bank with direct input on ways to scale up private finance in EMDEs.

One crucial piece that has been moved to the center of the table is blended finance.

In recent years, development banks and other public institutions have begun to team with large developed market financial corporations to blend the public and private resources available to the EMDE transition in more creative and targeted ways.

The Climate Investment Fund’s original financing of the Bhadla Solar Park is just one example. In another notable case in 2022, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency issued a $98 million guarantee to refinance Egypt’s Benban Solar Park, the world’s fourth-largest solar facility (and the largest in Africa), in combination with other public and private financing.21 The Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), which debuted with a 2021 commitment to South Africa, feature similar alliances on a rolling country-wide by country-wide basis.

Late last year at the 28th session of the UN Conference of the Parties (COP 28), UAE President Mohamed bin Zayed announced the creation of a $30 billion climate finance vehicle that takes these efforts to another level. This ALTÉRRA Fund employs a blended-finance concept known as catalytic capital designed to kickstart—and crowd-in—private capital for transition investing in EMDEs.

The concept is as simple as it is effective: In a catalytic arrangement, the fund’s sponsor makes a significant investment to a pool of capital and caps its own return on that investment, thereby raising the potential return for other private investors in the fund while simultaneously lowering the cost of capital for developers. By directly increasing the portion of the potential return offered to the other investors, significantly more investors are expected to commit to such a fund, creating a significant multiplier on the amount of capital available to support the EMDE transition. Such larger pools, with specific EMDE transition-focused mandates, will make the investments that—while very attractive from a risk-return perspective—previously struggled to secure capital.

“We think this could be transformational for the EMDE energy transition,” says Carney. “The emerging and developing world needs $1 trillion a year in external financing within the next several years to make the transition to net zero. Catalytic capital can help fill that gap by mobilizing more private investors to invest and bring scale to the transition in countries that have struggled to attract both in the past.”

What types of projects could use catalytic capital to tap these broader pools of private capital?

India offers another instructive example. As much progress as the country has made in bringing more renewable projects online, it still faces something of a “chicken-or-the-egg” problem. Developers must have funding in place to be able to secure capacities in state-run auctions that award long-term renewable offtake contracts. At the same time, most financiers require developers to have long-term agreements finalized before putting shovels in the ground, even for early-stage development. With the lengthy permitting and legal reviews that follow a successful bid, many projects are effectively delayed by three to four years.

One use of catalytic capital, then, could be to switch up the order: putting shovels in the ground first, and bidding for and finalizing contracts closer to completion. While such an approach introduces some degree of offtake risk (selling power in the spot market or under a short-term contract instead of to a pre-secured longer-term offtake), it also dramatically reduces the delivery time—and raises the upside. Established developers like Brookfield could manage the offtake risk with (often-lucrative) short-term contracts and bide their time for securing more favorable long-term contracts. In combination, a developer could forward-sell the renewable assets two to three years post-commissioning to credible counterparties looking to own derisked assets. These include a growing contingent of high-quality corporate customers that seek dedicated clean sources to power friend-shoring initiatives aimed at diversifying supply chains.

From the perspective of the investors, catalytic capital—and its ability to support large pools of EMDE-focused transition capital—can provide the missing ingredient that makes such optionality possible and creates the potential for higher returns. And India gains a new mechanism for accelerating the pace of renewable projects to meet its goals.

Multinational Corporations Are Demanding Clean Energy

The corporate appetite for clean energy isn’t only growing in India. Developed market-based multinationals have big manufacturing and distribution footprints throughout Asia, emerging Europe, Latin America and Africa. In many cases, the companies established their facilities decades ago to take advantage of lower labor costs and proximity to natural resources and growing consumer markets. Now, these companies have urgent transition goals to meet across their global platforms and are anxious to partner with large established funders and operators like Brookfield to build out the renewable capacity in all their markets.

While some renewable projects used to power a manufacturing facility can be built “behind the meter” adjacent to the customer’s plant, that won’t always be the case. In some scenarios, the grid needs to be able to receive the power and account for it, so the developer and customer can get credit for it. Attractive as they are, these projects remain subject to many of the usual country dynamics that have put EMDE projects outside the scope of most private market investors. Catalytic capital and its ability to create large focused EMDE pools of capital can help solve for that.

Recently, one large multinational reached out to us: Having worked with Brookfield to establish a handful of long-term offtake contracts in India, it wanted to know whether we could roll out the same model in their other markets, like Brazil, Chile, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Recently, one large multinational reached out to us: Having worked with Brookfield to establish a handful of long-term offtake contracts in India, it wanted to know whether we could roll out the same model in their other markets, like Brazil, Chile, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Brazil and Chile: No Time to ‘Waste’

Brazil and Chile provide more examples of the potentially transformative effects of catalytic capital. These are two of the most advanced of all the EMDE transition markets. Still, even these countries have long roads ahead of them.

Chile has approximately 4.6 gigawatts of installed coal capacity, much of it in the early stages of its useful life.22 The government has made a strict commitment to decommission all coal plants within the next 15 years. The phaseout of coal and other fossil fuel utilities is a hugely capital-intensive endeavor. But it also comes with the potential for higher returns, given the discounts at which such assets (including existing customer rate bases) can be acquired and the ongoing need (and often premium paid) for on-demand fossil fuel power to back up weather-dependent clean sources.

One utility on our radar in Chile has a clearly articulated roadmap for transitioning from largely heavy fuel oil to largely renewable generation in the next decade. It has many of the necessary elements for success, including recurring and predictable revenues to support the development of renewables, save for one: a credible partner experienced at executing a business transformation, with sufficient capital to get it started.

In a related vein, both Brazil and Chile have heavy industries that, like such sectors everywhere, remain dependent on fossil fuels to generate the higher temperatures needed to manufacture their outputs.

Brazil’s plan to decarbonize its steel and cement industries is part of the reason it has earmarked regions with large-scale renewable power for green hydrogen production. The hope is that the plentiful hydro, wind and solar power generated there might help to lower the production costs to where the green gas produced is competitive with coal or natural gas as an industrial input.

Brazil and Chile also have another resource to throw at their decarbonization efforts: the generative capacity of their waste.

Chile ranks as the world’s third-highest producer of waste per person,23 while Brazil boasts some of the largest landfills on the continent. These facilities are under increasing pressure from their governments to capture the millions of metric tons of methane and carbon dioxide they release into the atmosphere each year. Recent advancements in capture and processing technologies have, meanwhile, increased the viability of turning that gas into a productive green industrial-use biofuel source.

Given the carbon tax regimes emerging around the world—led by the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which in 2026 will start phasing in levies on imported steel, cement and other key commodities based on their carbon intensity—domestic-based multinational producers could increasingly be sourcing green products and fuels to avoid such levies. Here, catalytic capital can help spur investment in established technologies to allow them to scale in these markets, with attractive upside for investors.

Southeast Asia: The Next Frontier

Southeast Asia is another important investment frontier where new capital structures can help to catalyze markets at varying points in their transition.

In Thailand, a sizeable existing renewable industry and large, tech-savvy workforce have contributed to a surge in data centers to service the region’s exploding web traffic—along with the heavy energy usage such centers bring. Many of the centers are being built by Microsoft, Amazon and other global digital powerhouses who are now on the clock to fulfill negative-carbon commitments.

Malaysia has a similar data center boom underway. Malaysia is next door to Singapore, a developed market whose demand for renewable energy stands in direct contrast to the limited land it has on which to build solar and wind farms. Despite Malaysia’s in-market frictions, Singapore thus becomes a prime secondary market for every extra megawatt a Malaysian project can produce and transmit.

Just across the Singapore Strait, Indonesia would stand to benefit from the same enticing demographic and geographic advantages, if it weren’t one of the most challenging markets renewable operators and funders face today.

As the world’s largest coal exporter and one of the largest producers of liquefied natural gas in Southeast Asia, the Indonesia fossil fuel sector is deeply entrenched in the country’s domestic power mix. A single national utility controls the authorization of new projects while consumer incentives largely center around lowering consumer energy costs—including by subsidizing power produced by gas and coal. In the past year, the government has come out strongly in favor of changing those dynamics, with a stated goal of increasing renewables’ share in Indonesia’s power generation to 40% by 2030. In these next early phases of that transition, we see opportunities for experienced operators who can leverage global expertise as this market grows.

We also see the potential for early wins in Indonesia’s transportation sector. Another challenge the country faces is a severe undercapacity of last-mile transmission. Electric transport has grown in popularity, but widespread adoption faces even more of a charging-capacity challenge than in other countries—because even if more charging stations were built, there is no way for them to connect to the grid yet. That’s why a key transitional solution could be centralized charging-and-battery swap centers, as they are in China. Based on our previous experience in China, we see this as another opportunity.

It’s hard to overstate the impact that scaled, targeted infrastructure investments of this kind could have on a market like Indonesia. For a nation of 275 million people, Indonesia has a relatively small (17.1 million) number of cars. But it has 125 million motorbikes,24 and almost all of them are powered by internal combustion engines (ICEs).25 Even for many ordinary Indonesians, the cost of replacing an ICE bike with an electric one would be manageable, especially compared to buying an EV. The big hurdle is charging—which was also the case with China’s 85 million motorbikes about a decade ago. Today, the vast majority of new motorcycles and mopeds sold on the mainland are powered by electricity.26

Investment Can Create a Virtuous Circle

Emerging markets and developing economies are home to 85% of the world’s population.27 They account for more than half the world’s energy consumption (headed toward 70% by 2050).28 It’s obvious there is no route to net zero that doesn’t lead through these regions.

Private investors who have deployed capital to developed market transition projects can appreciate that the impact of their investments could be even greater in EMDEs, especially in the most carbon-intensive markets. The energy growth potential, lower input costs and natural advantages that many of these markets offer are compelling.

Now, with the acceleration in corporate demand plus the recent progress in blended finance and catalytic capital, many of these hurdles are clearing. As a result, private market investors have clearer on-ramps to put their capital to work in EMDEs, and multinational corporations can more easily partner with global renewable power providers at scale in these regions.

There is no need to “boil the ocean,” as it were, to mitigate EMDEs’ contribution to the warming of the seas and atmosphere. Specific, targeted and potentially highly remunerative investments can have hugely catalyzing effects. The new catalytic structures aim to create large pools of appropriately mandated capital to support the transition. The structures nest within the larger evolving climate finance ecosystem, so that the same investors benefitting from catalytic capital may see additional upside from public finance support as well as innovative carbon market instruments.

Increasing the flow of capital to EMDEs—and leveraging deep global operating experience in renewable power—can be transformational on the ground by helping to manage those dynamics that have limited investment in the past. This will not only spur more Bhadla-scale projects but also generate opportunities to earn attractive risk-adjusted returns.

Endnotes:

1. IEA, “Scaling up Private Finance for Clean Energy in Emerging and Developing Economies," June 2023.

2. Blackridge Research, "India Builds World’s Largest Solar Park at Bhadla in Rajasthan to Decarbonize Its Energy Production," July 30, 2023.”

3. Business Insider, “India is harnessing renewable energy through the world’s biggest solar farm. Here’s how it happened,” November 22, 2022.

4. PR Newswire, “Eccopia Expands Bhadla Park Cloud-based Robotic Cleaning Footprint with Additional 500 MWp,” July 2, 2018.

5. Blackridge, July 30, 2023.

6. Energy Digital, “Top 10: Largest Solar Power Parks,” May 30, 2023.

7. In “The promise and perils of the solar energy boom,” published in Wired on October 15, 2021, it was estimated that the project could power 4.5 million Indian homes, based on installed capacity at the time of 2.25 gigawatts. Additions to the park since have taken total installed capacity to 2.7 gigawatts.

8. Blackridge Research, EcoHubMap, “Solar power project at Bhadla, India,“ 2024.

9. Foreign Affairs, “Can India Become a Green Superpower?” July/August 2023.

10. The New York Times, “A New Surge in Power Use in Threatening U.S. Climate Goals,” March 14, 2024.

11. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, global electricity demand is expected to increase 33% by 2050, with 75% of that growth coming from EMDEs, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Information Administration, “EIA projections indicate global energy consumption increases through 2050, outpacing efficiency gains and driving continued emissions growth,” October 11, 2023. International Energy Agency, “Net Zero by 2050,” May 2021 (page 39).

12. IEA, June 2023.

13. IEA, "Reducing the Cost of Capital,” February 2024.

14. G20 Independent Experts Group, “Strengthening Multilateral Development Banks: The Triple Agenda,” July 2023.

15. IEA, “Renewables 2023: Analysis and forecast to 2028,” January 2024.

16. IEA, “Reducing the Cost of Capital: Strategies to unlock clean energy investments in emerging and developing economies,” February 2024.

17. Ibid.

18. Foreign Affairs, “Can India Become a Green Superpower?” July/August 2023.

19. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, “2021 Cost of Wind Energy Review,” December 2022; Wind Europe, “Wind energy is the cheapest source of electricity generation,” March 29, 2019; BloombergNEF, 2H 2023.

20. Currency risk should be somewhat lower going forward, with the apparent end of the dollar strengthening supercycle. That said, the need for robust currency hedging strategies is another element that can add to the cost of capital for EMDE transition projects.

21. Afrik 21, “EGYPT: MIGA guarantees $98 million to refinance six solar farms in Benban,” July 5, 2022.

22. Energy Partnership Chile-Alemania, "Phasing out Coal in Chile and Germany – A Comparative Analysis," June 2021.

23. Sensoneo, “Global Waste Index 2022,” November 8, 2023.

24. Statista 2024.

25. The Jakarta Post, "Only a fraction of Indonesia’s motorbike fleet seen to be electric by 2030,” February 27, 2023.

26. According to the latest report from Statista 2024, Chinese consumers were projected to purchase over 40 million electric two-wheelers in 2022; that compares to the 6.16 million gas-powered units purchased the same year, according to a September 2023 report prepared for the Italian Trade Agency.

27. WorldData.info (last modified January 2024).

28. Exxon Mobile, “Energy demand: Three drivers,” January 8, 2024.

Disclosures

This commentary and the information contained herein are for educational and informational purposes only and do not constitute, and should not be construed as, an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities or related financial instruments. This commentary discusses broad market, industry or sector trends, or other general economic or market conditions. It is not intended to provide an overview of the terms applicable to any products sponsored by Brookfield Asset Management Inc. and its affiliates (together, "Brookfield").

This commentary contains information and views as of the date indicated and such information and views are subject to change without notice. Certain of the information provided herein has been prepared based on Brookfield's internal research and certain information is based on various assumptions made by Brookfield, any of which may prove to be incorrect. Brookfield may have not verified (and disclaims any obligation to verify) the accuracy or completeness of any information included herein including information that has been provided by third parties and you cannot rely on Brookfield as having verified such information. The information provided herein reflects Brookfield's perspectives and beliefs.

Investors should consult with their advisors prior to making an investment in any fund or program, including a Brookfield-sponsored fund or program.