Wittleder: An often-overlooked area of the transition space is “demand side” decarbonization, which is driven by the consumer and cost. As a result, more corporations and communities are looking to meet consumers’ demand and reduce costs by increasing energy efficiency, lowering energy consumption and reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

This has created investment opportunities in residential energy infrastructure, submetering and residential smart metering. For instance, we are investing in platforms in both Europe and North America that provide energy-efficient products and services. These offer consumers significant cost savings to the prevailing alternatives.

Q: Where are infrastructure debt opportunities intersecting with deglobalization, or the third D?

Wittleder: Global supply chain disruptions and recent geopolitical events have led governments and corporations alike to prioritize their supply chain resiliency—particularly for baseload power, critical manufacturing and logistics.

For example, LNG will continue to play a key role in providing global energy security. This means that globally, infrastructure will be needed in critical locations to process, transport and distribute natural gas.

There is also an increasing focus on bringing important manufacturing processes onshore, such as semiconductor factories. Both the U.S. and Europe have announced programs to support the buildout of semiconductor facilities, committing upwards of $100 billion to back the reshoring of this manufacturing from Asia.

Finally, transport infrastructure and logistics networks must also evolve to become more resilient in the face of long-term rising demand. These assets and networks will require significant capital—both to clear up bottlenecks and to add capacity.

Q: What opportunities are you seeing in utilities?

Wittleder: Municipal and state-owned utilities are increasingly looking to privatize or find alternative funding to meet the growing demands on their electricity transmission and distribution systems. It’s crucial to ensure that grids have the built-in flexibility to transmit and distribute energy from renewable sources. Privately owned utilities looking to achieve this same flexibility may also face capital constraints. They are then turning to private capital providers that have the experience to fund growth projects in this sector. Many utilities are also realizing that the efficiency benefits gained from smart metering, energy storage and other solutions will require substantial capital to deploy in the near term.

Simes: Another way that local municipalities can achieve their decarbonization goals is through district energy. These assets provide heating or cooling to multiple buildings from centralized facilities through a common and interlinked distribution system. They generally cost less and are more reliable than boilers or chillers contained within individual buildings. The systems have strong infrastructure characteristics through either their essential and cost-efficient nature, or through the use of long-term, capacity-based contracts with fuel cost pass-through, creating stable revenue streams.

Q: Any other sector opportunities to consider?

Wittleder: While not the same activity level as power and data, opportunities in transport infrastructure continue to arise. Roads, rail, marine and logistics businesses are looking to add capacity to their networks and to meet increased demand while maintaining a high quality of service.

For example, many regional mid-market transportation assets in the U.S. have been family-owned, and over time are being aggregated by institutional investors to enhance synergies across networks. We have financed such rollup opportunities, supporting the institutionalization of that service.

From an investor’s point of view, the long-term value and typical links to inflation mean that such assets tend to withstand periodic traffic fluctuations, provided they have sufficient near-term liquidity.

Simes: We also continue to see opportunities in the midstream sector, where natural gas is proving to be an essential transition fuel to support the growth of intermittent renewable generation as well as enhancing energy security, leading to significant investment requiring private capital solutions. Given our ability to move quickly, we have been able to provide sponsors with our type of financing as they look to accrete returns and reduce their equity tickets.

Q: Could you discuss how you are weighing infrastructure sectors today in the context of portfolio construction?

Simes: We generally have higher weightings on the sectors with greater activity, so today, those are data—including wireless infrastructure, fiber networks and data centers—and renewable power.

Yet, we are very mindful of building a diversified portfolio. For instance, if we zoom out and see a concentration in data, then we’ll drill down and consider things like how much of that is laying fiber-optic cable to homes? How much of that is cell towers serving mobile phones? How much is data centers? We make sure the risks are not correlated.

Wittleder: We can also drill down further in each of the assets. For example, are we concentrated in any one region or offtaker, the party that's paying to use those sites?

By engaging in this deeper analysis, we can both focus on active sectors and make sure our portfolio remains diversified.

Q: Any final thoughts?

Simes: Yes, I think investors should consider the importance of structuring within the infrastructure debt space. Unlike corporate credit, infrastructure deals tend to be much more complex. A toll road is quite different from a wind farm, so we must drill down into each asset and then structure the loan accordingly. This is one reason why infrastructure debt tends to be insulated from the boom-bust cycle of corporate credit.

Wittleder: There's also a significant amount of diligence required when underwriting infrastructure debt. A lender needs to understand how each asset works, how the contracts work, the regulatory environment, the technical and operational aspects, etc. This also limits competition, since not every investment company has the institutional knowledge or technical expertise needed to assess these risks.

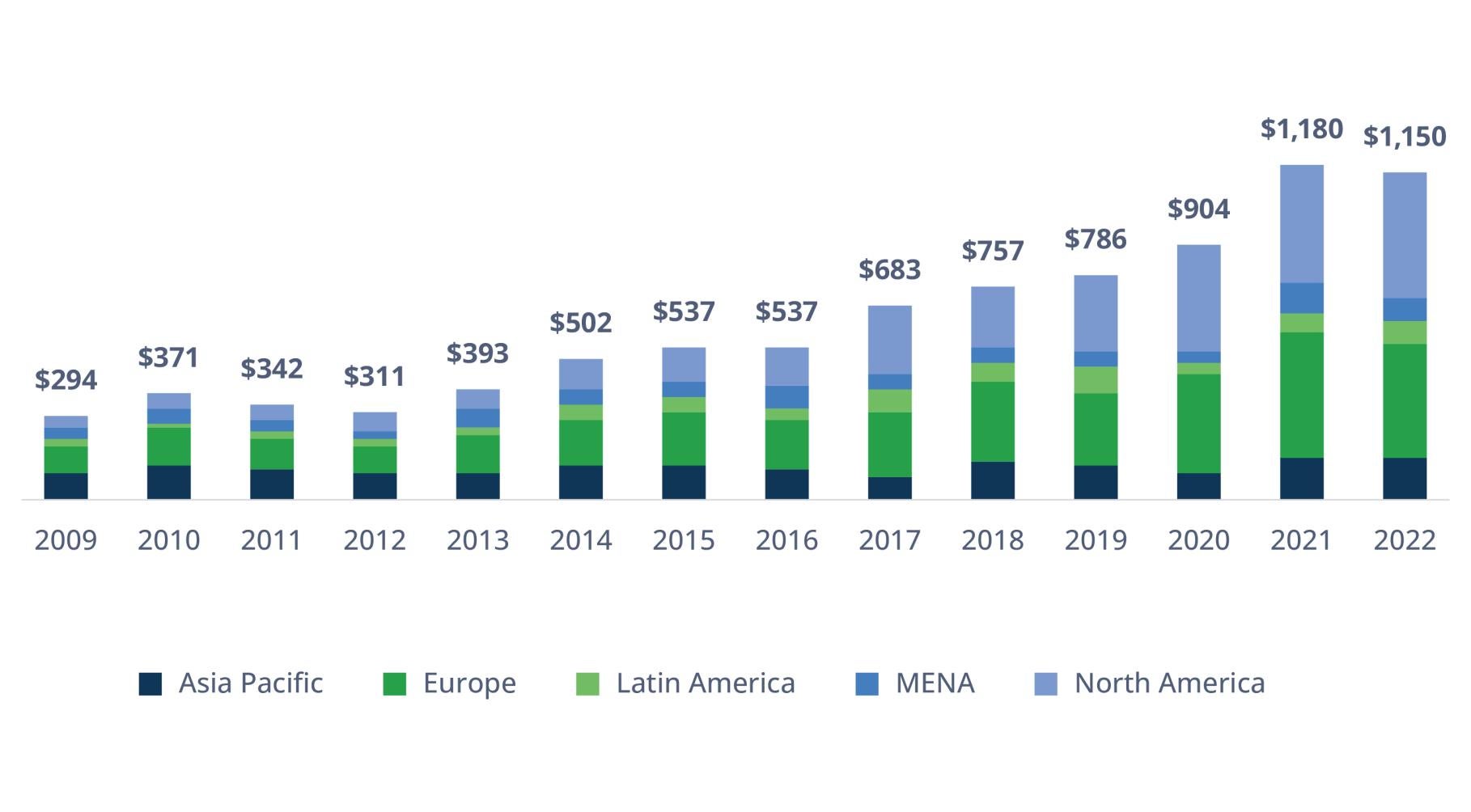

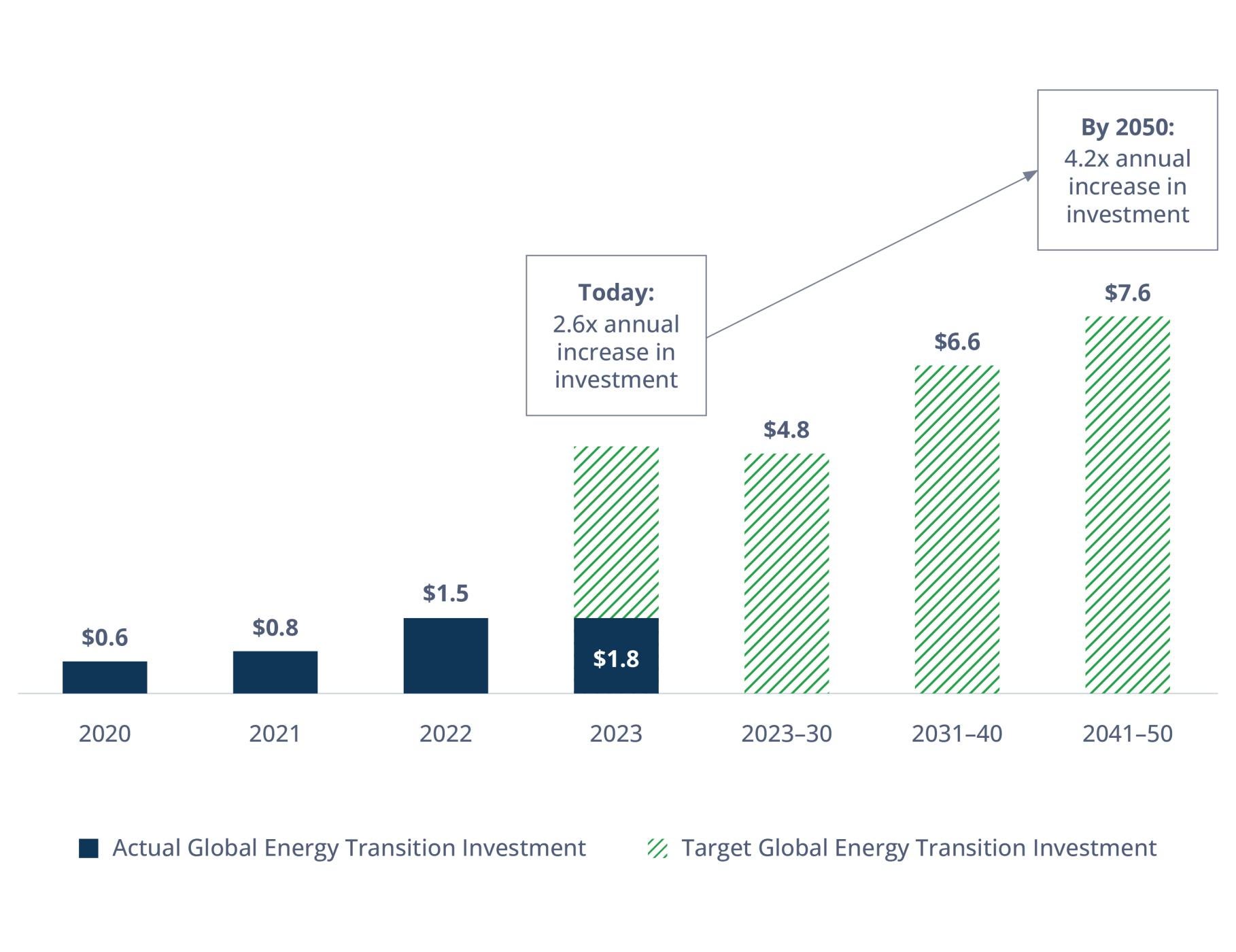

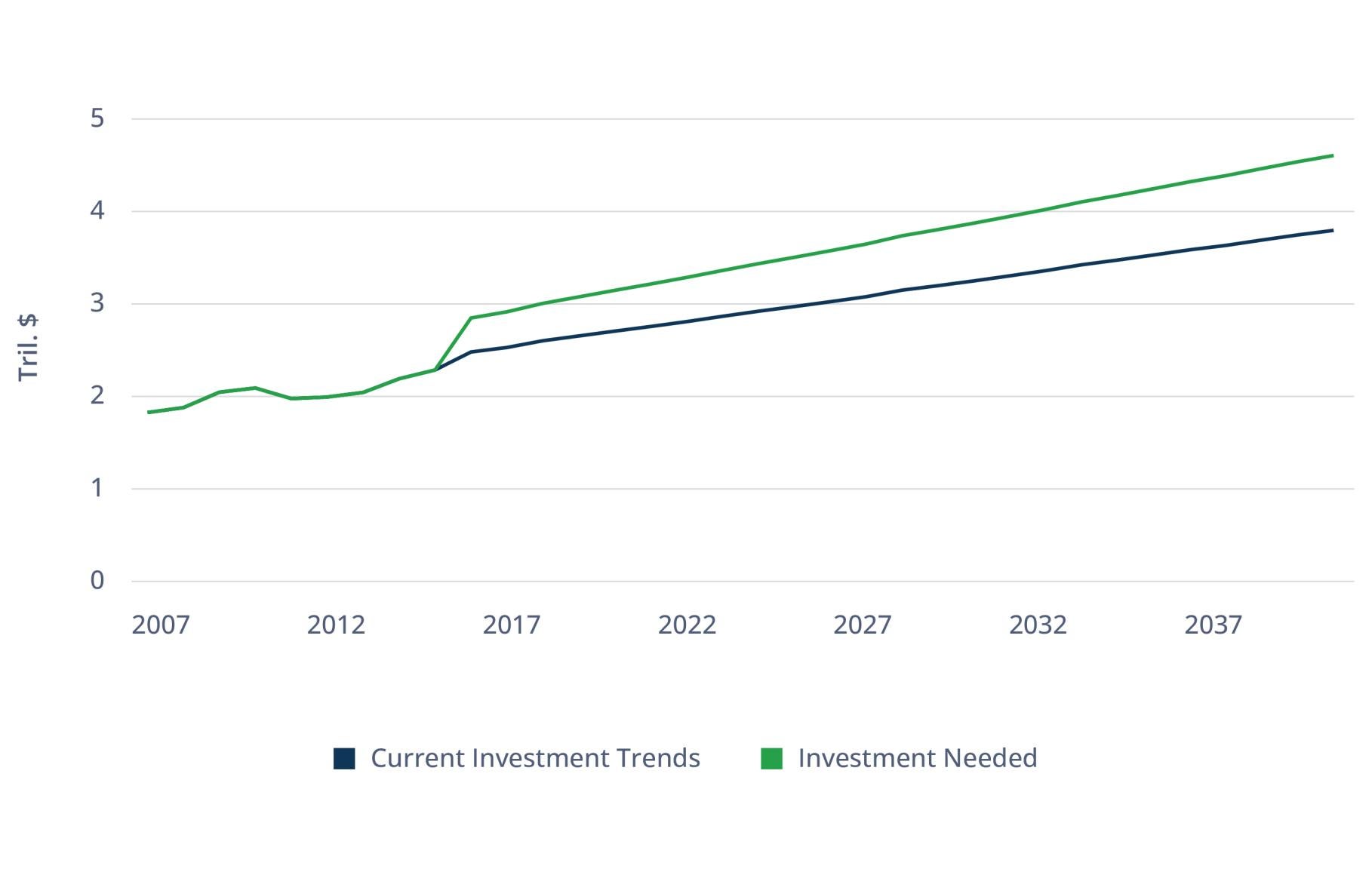

Simes: Yet these complexities are part of what makes infrastructure debt so attractive—when you do it right. And we’re seeing many more opportunities to do so. Estimates of the required infrastructure investment needed globally are massive across both developed and emerging economies. Approximately $94 trillion of cumulative infrastructure investment will be needed through 2040 (see Figure 4).

In other words, we have a lot of work ahead of us—and we look forward to it.